There’s a lot to talk about regarding Intel’s 12th Gen ‘Alder Lake’ processors. The company says this is its biggest architectural change in a decade, and if anything, that’s an understatement. Intel frankly hasn’t had anything this new or intriguing to talk about in many years (one decade ago is when the much-loved ‘Sandy Bridge’ generation debuted), and it’s almost like wiping the slate clean. Now, the company gets to start fresh after years upon years of problems that snowballed into each other even as sole rival AMD has been notching up success after success. The 12th Gen Core family pulls off a jump in performance thanks to the combined strengths of two different types of cores, a native design for a 10nm manufacturing process, and a brand new platform that leverages new high-speed interconnect standards.

Intel is kicking off the 12th Gen product roadmap with flagship desktop CPUs for gamers and enthusiasts – a big departure from the company’s focus on thin-and-light laptops for the past several years. All the CPUs that have launched so far are unlocked and overclockable, which tells you who they’re aimed at. More mainstream options for everyday work will be announced early next year.

We’ve come a long way from quad-core CPUs at the top end just a few years ago, and it’s all thanks to competition. With up to 16 cores (and 24 threads), Intel might now seem to be competitive with AMD’s 16-core desktop flagship, the Ryzen 9 5950X. Things aren’t quite that simple though, since heterogenous cores can’t really be compared. Still, Intel is promising an impressive 19 percent performance gain compared to the previous generation and there are benefits with regard to power efficiency to be explored as well.

Here’s an in-depth look at the 12th Gen Core ‘Alder Lake‘ CPU architecture as well as our benchmark test results and analysis of Intel’s new push into the performance and gaming enthusiast PC market.

![]()

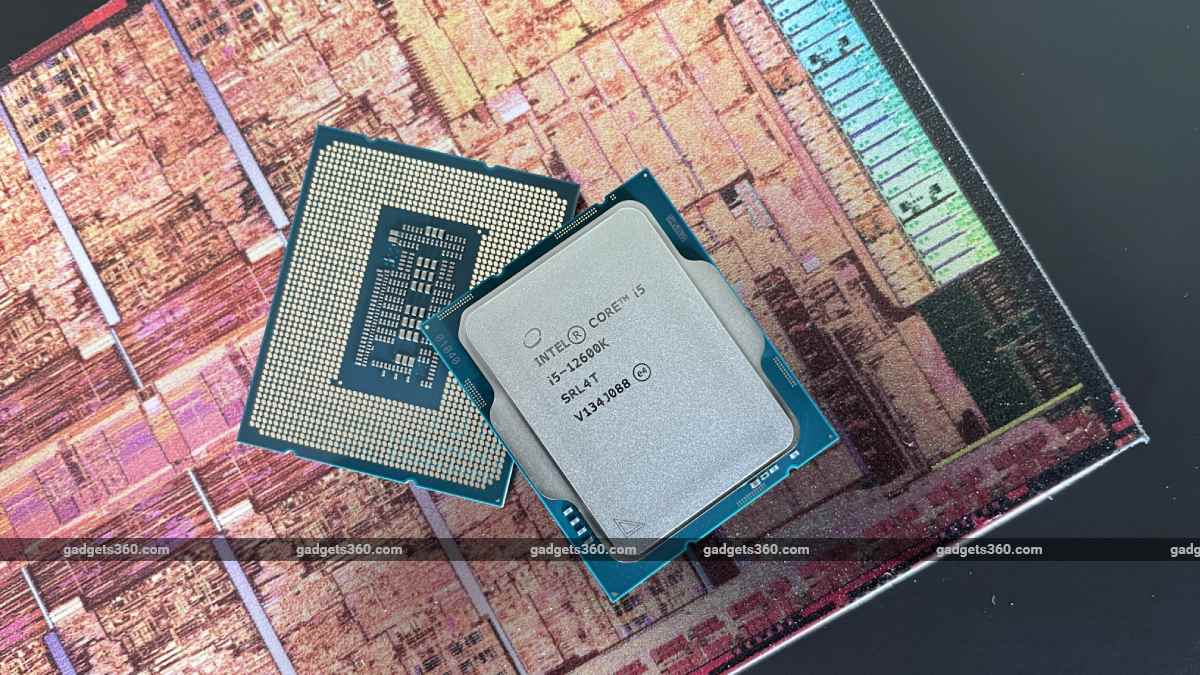

12th Gen Intel Core CPUs are physically larger than their predecessors, requiring a new LGA1700 socket

Intel 12th Gen Core ‘Alder Lake’ architecture and specifications

The 14nm node saga, which has stretched on since the introduction of the Broadwell (5th Gen Core) die shrink in 2014, is finally over and done with, at least as far as Intel’s desktop CPUs go. The 11th Gen ‘Rocket Lake’ family was a 10nm design backported to 14nm in order to get it into customers’ hands amid ongoing 10nm production constraints, and now hopefully those have been solved for good.

Intel calls its current 10nm process implementation ‘Intel 7‘, which is a pretty blunt attempt to position it as technologically on par with competitors’ mature 7nm efforts. At this scale, the sizes of individual transistors aren’t necessarily reflected by such names, and with a move to modular tile-based CPU designs, they don’t all have to be the same size anyway. Nevertheless, ‘Intel 7′ tells us that the company has renewed confidence in its own fabs and foundries, even as we see news that the next-generation node will also be delayed.

The bigger news is that Intel has now separated its architecture and manufacturing efforts to the point that it can mix and match different bits of a CPU’s components such as cores, the integrated GPU, cache memory, IO logic, security subsystems, and more. Different implementations of ‘Alder Lake’ for different target markets, ie desktop PCs, laptops, and ultra-mobile devices, will have different combinations of these components.

![]()

All six 12th Gen Core CPUs launched so far are unlocked and overclockable

For now, we have the top-of-the-line Core i9-12900K desktop CPU with eight “Performance” cores (with their own codename, ‘Golden Cove’) and eight “Efficient” cores (‘Gracemont’). The P-cores, in Intel’s shorthand, are what we’re familiar with – Golden Cove is the successor to ‘Willow Cove’ which all 11th Gen 10nm CPUs were based on. Gracemont is the current derivative of the former Intel Atom CPU lineup – although the Atom name has been retired, ‘-mont’ cores have been the basis of many of Intel’s embedded CPU offerings as well as low-end Pentium Silver and Celeron CPUs over the years. Most recently, Intel’s first hybrid offering, ‘Lakefield‘, also combined previous-gen ‘-cove’ and ‘-mont’ cores.

That’s a lot of codenames, and Intel is studiously avoiding the term ‘big.LITTLE’ which is rival Arm’s trademark, and goes back at least a decade. This of course refers to exactly the same concept – dividing work between a group of high-performance but power-hungry cores as well as low-power cores based on which are more suitable, in order to maximise power as well as efficiency. Intel itself had rejected the idea of doing so on several occasions in the past, saying that it’s possible to design one type of core that can scale adequately in terms of power consumption as well as performance. Clearly, though, the company has changed its mind.

In order for an operating system to know which cores to target and when to migrate threads from one type of core to another, Intel says it has developed a more robust and responsive real-time scheduler, called Thread Director. As of now, this works only with Windows 11, and neither Intel nor Microsoft have plans to bring it to Windows 10. A solution for Linux is currently in development. According to Intel, you should expect a slight performance drop with Windows 10, but Alder Lake CPUs will still be perfectly usable.

![]()

One huge change with Alder Lake hybrid CPUs is that only the P-cores support Hyper-Threading, which is the ability to run a second simultaneous thread when resources allow for it. Therefore, the 16-core Core i9-12900K is capable of executing 24 threads, not 32. Interestingly, while the the P-cores get top priority, the E-cores come next, and only if they are saturated will a P-core be assigned a second thread. Windows 11 can leverage Thread Director to decide what gets priority where – for example you could be encoding media in the background while getting on with other tasks.

It doesn’t seem as though users will be able to override this and manually specify whether any particular program or task should be given preference for each core type. It will be interesting to see how upcoming 12th Gen laptop CPUs add battery life to the list of variables that are being juggled by Windows 11. What’s also odd is that Intel says heavily multi-threaded workflows such as video encoding will prefer E-cores, though conventional logic suggests that P-cores should be able to muscle through such tasks quicker.

There’s one more issue at play here – some older software doesn’t recognise the heterogenous cores as all belonging to the same CPU. You might encounter some compatibility issues – the Denuvo game DRM scheme has recently been flagged as incompatible, locking people out of at least 50 older games because it thinks system specs have changed due to piracy. In such cases, you can lock the E-cores out completely through your motherboard BIOS (and Intel says you can even assign the Scroll Lock key on your keyboard to toggle this).

Intel has also maintained that the AVX-512 instruction set, a feature heavily touted since Ice Lake for its use in accelerating AI workloads, has been disabled. This was purportedly because only the P-cores can support it and there needs to be instruction parity between core types. However, it now seems that disabling E-cores in your motherboard BIOS will allow AVX-512 to be enabled – so there’s a tradeoff there too.

![]()

Platform-level connectivity gets a boost with the Z690 chipset

While each P-core has 1.25MB of L2 cache memory, the E-cores are arranged in clusters of four, each with a shared 2MB L2 cache. These feed into a common L3 cache. Intel also publishes different base and turbo speeds for each core type, and higher-tier CPU models additionally support Intel’s Turbo Boost Max feature that assigns “favoured cores” which can be boosted even higher. That means clock speed is now extremely muddled and not necessarily a useful metric when it comes to comparing specifications. We have a 125W base TDP, and for the first time Intel is also publishing power target figures for sustained load, which can go up to 241W for the Core i9. If you have a capable enough thermal solution, you’ll be able to run at Turbo speeds indefinitely – not just in bursts.

On the Core i9-12900K, the eight E-cores run between 2.4GHz and 3.9GHz, while the eight P-cores run between 3.2GHz and 5.1GHz (all cores) or 5.2GHz (favoured cores). There’s 14MB of L2 cache and 30MB of L3 cache memory.

The Core i7-12700K loses four E-cores so you get eight P-cores and four E-cores (totalling 20 threads). Peak power usage is rated at 190W. The Core i5-12600K has six P-cores and four E-cores, with a 150W peak power draw rating.

All three CPU models feature integrated Intel UHD Graphics 770 integrated GPUs, based on the Xe-LP architecture. Nothing is new compared to the 11th Gen’s integrated UHD 750 GPU, except for lower base and higher boost clocks. All three CPUs also have -F suffix variants which lack integrated graphics and are priced a little lower on paper.

![]()

Many cooler manufacturers offer retrofit kits for the LGA1700 socket so you can reuse existing ones

Intel 12th Gen Core ‘Alder Lake’ Z690 platform

Considering how much has changed with Alder Lake, it’s no surprise that a new socket and new motherboards will be required. These CPUs are physically larger than most previous mainstream Intel desktop CPUs, and are now rectangular rather than square. The pad count has jumped to 1700 (from 1200) and so there’s a new LGA1700 socket. Hopefully, this should last for at least one more generation. Most coolers designed for previous-gen motherboards should work, but you will most likely need a retrofit kit – most brands will update their offerings or offer a simple adapter kit. It would be best to check with your cooler’s manufacturer, since there could be rare exceptions due to differences in the contact surface area.

The biggest news for most users will be the introduction of DDR5 RAM. This promises significant jumps in bandwidth, maximum capacity, and power efficiency. DDR4 has been entrenched for a very long time but also isn’t likely to disappear anytime soon – DDR5 RAM kits are currently hard to find and quite expensive, especially in India. You’ll be able to buy Z690 motherboards with either DDR4 or DDR5 slots (dual-channel in either case) – no manufacturer has shown off a hybrid board yet. That means you’ll have to commit to one standard or the other upfront.

Intel has also managed to be the first to introduce PCIe 5.0, which doubles internal IO bandwidth compared to PCIe 4.0. There aren’t any components such as SSDs that can take advantage of this yet, but at least you get to share that bandwidth between devices so more can operate at high speed. Motherboards can have one PCIe 5.0 x16 slot or route that bandwidth to two PCIe 5.0 x8 slots, and these connect directly to the CPU. That’s in addition to four PCIe 4.0 lanes that can now be dedicated to an SSD, plus the Z690 controller itself hosts 12 PCIe 4.0 lanes and another 16 PCIe 3.0 lanes for various components. Bandwidth between the CPU and the Z690 has doubled as well.

Also on the connectivity front, there’s now support for up to four USB 3.2 Gen2x2 (20Gbps) – this shouldn’t be confused with USB4 Gen3 which can also achieve 20Gbps with the same Type-C connector. You can have up to 10 USB 3.2 Gen2 (10Gbps) ports as well, between the rear panel and additional headers. PCIe and M.2 slot configurations will depend on motherboard manufacturers. Intel has implemented a Wi-Fi 6E controller, which is a step up from Wi-Fi 6, and there’s still integrated Gigabit Ethernet. Of course things like Intel Optane are supported, and all Z-series motherboards are overclocking-friendly.

Lower-end platforms will be introduced when Intel launches non-K 12th Gen CPUs, and we don’t yet know how they will be differentiated and whether certain features will be exclusive to the top-tier Z690. Obviously with the split between DDR4 and DDR5, there will be a huge variety of Z690 motherboards to choose from. Asus, Gigabyte, MSI, ASRock, and some smaller brands have already introduced a variety in the Indian market.

![]()

Components used for the review of the Core i9-12900K and Core i5-12600K

Asus TUF Gaming Z690-Plus WiFi D4 motherboard and Strix LC II 360 ARGB AIO cooler

For this review, Asus sent across one of its more affordable Z690 motherboards, the TUF Gaming Z690-Plus WiFi D4, as well as a Strix LC II 360 ARGB AIO cooler with an LGA1700 adapter. The D4 suffix indicates that this board will only work with DDR4 RAM, which is fitting given the segment it targets. While not quite as tricked-out as flagship models that sell for as much as Rs. 65,000, this motherboard should be able to take care of most of what enthusiasts need, at a far more approachable price of Rs. 25,000.

The board layout has no big surprises. It has four slots for a maximum of 128GB of RAM with overclocking support going up to DDR4-5333. There are chunky VRM heatsinks around the CPU socket, which might interfere with extremely large air coolers, and you’ll want to be careful of a few sharp corners.

I did note a lack of little conveniences like an LED diagnostic display and surface-mount power and reset buttons, which make initial assembly and working on an open bench easier. You also don’t get a secondary BIOS as a failsafe. On the plus side, Asus has developed an M.2 latch system that dispenses with the usual tiny screws, and you get heatsinks on all four M.2 slots.

The integrated rear IO shield is much appreciated and will make installation easier. There’s one USB 3.2 Gen2x2 (20Gbps) Type-C port, two USB 3.2 Gen2 (10Gbps) Type-A ports, and five USB 3.2 Gen1 (5Gbps) ports, one of which is Type-C and four Type-A. This board also has HDMI 2.1 and DisplayPort 1.4 video outputs, 2.5Gbps Ethernet, two terminals for the included Wi-Fi 6 antenna, optical S/PDIF audio output, and the standard five analogue 3.5mm audio jacks. Unfortunately you don’t get Thunderbolt at this price point, or external BIOS reset and update buttons. Bluetooth 5.2 is an invisible bonus.

![]()

The rear IO panel of the TUF Gaming Z690-Plus Wifi D4 offers a lot of connectivity

Internal headers will allow for up to four USB 2.0 ports plus high-speed front panel Type-A and Type-C ports. There are multiple ARGB control headers and four chassis fan connection points in addition to independent CPU fan and AIO pump headers. You do get RGB lighting but the tiny accents on one edge of the board and under the Z690 heatsink are actually quite easy to miss. There are only four SATA ports; two facing upwards and two facing sideways off the board’s edge.

There are four M.2 slots, all but one of which have heatsinks. The primary slot is fed by the CPU directly. Only one slot can work with an M.2 SATA SSD; the other three including the primary one are NVMe-only. The first PCIe slot is also wired to the CPU, and gets a full 16 lanes of PCIe 5.0 bandwidth. The second x16 slot as well as the one x4 and two x1 slots might have to share bandwidth with the M.2 slots depending on which ones you populate.

The UEFI BIOS is quite easy to navigate. You can see an overview in “easy mode” or dig deep into the menus, where you’ll find an array of options for controlling onboard features and considerable manual overclocking controls. Overall, the Asus TUF Gaming Z690-Plus WiFi D4 does lack some conveniences, but delivers plenty considering its price. If you aren’t an avid overclocker with an elaborate liquid cooling setup, and are planning to stick with DDR4 RAM, this could be a solid base to build upon.

Asus says that the Strix LC II 360 ARGB cooler (priced at Rs. 18,950 in India) will work with LGA1700 processors just fine as they are. Even so, new units will ship with a redesigned bracket, so you might want to make sure of this if you’re buying a new one. Everything comes neatly packaged in the box, and it’s easy to put the parts together. The instruction leaflet doesn’t cover things like push/pull orientation for the fans, or which way the radiator should be oriented depending on where you want to place it in your cabinet. Asus also could have used resealable bags with clearer labels for all the brackets, screws, and washers since several are included for both AMD and Intel mounts. On the bright side, there’s no separate controller unit for fan or RGB control and the wiring to your motherboard headers is straightforward.

![]()

You’ll need an adequate cooler if you want the Core i9-12900K to run at its highest speeds for sustained periods

Intel Core i9-12900K and Core i5-12600K performance

Both CPUs were tested with the same set of components, starting with the Asus TUF Gaming Z690-Plus WiFi D4 motherboard and Strix LC II 360 ARGB AIO cooler. The rest of the rig was comprised of a 2x16GB Corsair Dominator Platinum RGB DDR4-3600 RAM kit, a Sapphire Nitro+ Radeon RX 590 graphics card (removed when testing the CPUs’ integrated GPUs), a 2TB Kingston KC3000 PCIe 4.0 NVMe SSD and a 1TB Samsung SSD 860 EVO SSD, a Corsair RM850 power supply, and an Asus PB287Q 4K monitor.

All tests were run using a fresh installation of Windows 11, with all available patches installed and all drivers updated. This, plus the use of DDR4 RAM, and the fact that not all tests might be updated to recognise and exploit heterogenous cores, might reflect in some benchmark results. We have the previous-gen Core i9-11900K and Core i5-11600K to compare test results with, as well as some previous-gen and HEDT Intel and AMD CPUs (lockdown-related restrictions mean we don’t have Ryzen 5000 series scores to compare against yet). Click through to our previous reviews to see even more points of reference.

| Intel Core i9-1200K | Intel Core i5-12600K | Intel Core i9-11900K | Intel Core i5-11600K |

AMD Ryzen 9 3900X |

Intel Core i9-10980XE | AMD Ryzen Threadripper 3970X | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPU tests | |||||||

| Cinebench R20 CPU single-threaded | 760 | 732 | 628 | 595 | 495 | 452 | 515 |

| Cinebench R20 CPU multi-threaded | 10,324 | 6,664 | 5,927 | 4,292 | 6,785 | 8,729 | 17,069 |

| Cinebench R23 CPU single-threaded (10 mins) | 1,982 | 1,909 | 1,676 | 1,542 | NA | NA | NA |

| Cinebench R23 CPU multi-threaded (10 mins) | 26,820 | 17,395 | 15,373 | 11,094 | NA | NA | NA |

| PCMark 10 standard | 8,174 | 7,645 | 7,474 | 5,036 | 6,597 | 6,914 | 6,637 |

| PCMark 10 extended | 9,121 | 8,608 | 8,466 | 8,137 | 6,807 | 7,967 | 7,681 |

| 3DMark Fire Strike Ultra (physics) | 40,355 | 28,824 | 26,716 | 22,328 | 27,471 | 28,111 | 22,010 |

| 3DMark Time Spy (CPU) | 13,016 | 10,329 | 11,000 | 8,446 | NA | NA | NA |

| Geekbench 5 single-threaded | 1,749 | 1,827 | 1,777 | 1,654 | NA | NA | NA |

| Geekbench 5 multi-threaded | 11,219 | 10,329 | 9,536 | 7,582 | NA | NA | NA |

| POVRay* | 29 seconds | 44 seconds | 55 seconds | 1 minute, 16 seconds | 41 seconds | 35 seconds | 18 seconds |

| VRAY CPU* | 32 seconds | 49 seconds | 54 seconds | 1 minute, 14 seconds | 48 seconds | 37 seconds | 20 seconds |

| Corona Renderer Benchmark* | 1 minute, 18 seconds | 1 minute, 37 seconds | 1 minute, 35 seconds | 2 minutes, 11 seconds | 1 minute, 19 seconds | 57 seconds | 29 seconds |

| WebXprt | 360 | 335 | 308 | 310 | 260 | 237 | 256 |

| Jetstream 2 | 236.138 | 233.186 | 209.32 | 196.946 | NA | NA | NA |

| Speedometer | 231 | 251 | 216 | 201.8 | NA | NA | NA |

| SiSoft SANDRA CPU arithmetic | 520.59GOPS | 362.87GOPS | 313.18GOPS | 224.44GOPS | 366GOPS | 496GOPS | 940.69GOPS |

| SiSoft SANDRA CPU multimedia | 1.55GPix/s | 1GPix/s | 1.3GPix/s | 948.64MPix/s | 1.26GPix/s | 2.13GPix/s | 3.31GPix/s |

| SiSoft SANDRA CPU cryptography | 18.35GBps | 15.74GBps | 14GBps | 16.88GBps | 18.09GBps | 25.65GBps | 41.42GBps |

| SiSoft SANDRA cache bandwidth | 485GBps | 332.25GBps | 429GBps | 351GBps | 589.9GBps | 701.53GBps | 1.73TBps |

| 7Zip file compression* | 1 minute, 51 seconds | 1 minute, 52 seconds | 1 minute, 37 seconds | 1 minute, 40 seconds | 1 minute, 33 seconds | 1 minute, 8 seconds | 56 seconds |

| Handbrake video encoding* | 25 seconds | 30 seconds | 32 seconds | 41 seconds | 35 seconds | 37 seconds | 30 seconds |

| Civilization VI AI benchmark (average) | 8.72 seconds | 8.76 seconds | 8.83 seconds | 8.87s | NA | NA | NA |

| Integrated GPU tests | |||||||

| Unigine Superposition 1080p Medium | 1,445 | 1,366 | 1,188 | 1,207 | |||

| 3DMark Time Spy | 874 | 819 | 698 | 702 | |||

| 3DMark Night Raid | 11,778 | 10,859 | 9,423 | 9,448 | |||

| Discrete GPU tests | |||||||

| 3DMark Fire Strike Ultra | 3,789 | 3,708 | 3,638 | 3,746 | |||

| 3DMark Time Spy | 5,439 | 5,326 | 5,290 | 5,200 | |||

| Far Cry 5 1080p Ultra | 81fps | 77fps | 82fps | 81fps | |||

| Far Cry 5 1440p Ultra | 56fps | 54fps | 58fps | 57fps | |||

| Assassin’s Creed Odyssey 1080p Very High | 57fps | 62fps | 61fps | 62fps | |||

| Assassin’s Creed Odyssey 1440p Very High | 41fps | 45fps | 45fps | 44fps | |||

| *lower is better | |||||||

The thing that jumps out first and foremost is how much of a jump there is in tests that can scale to any number of cores and threads. While the previous generation Core i9 flagship topped out at 8 cores and 16 threads, there’s obviously a lot to be gained just by having those counts go up to 16 and 24 respectively, irrespective of architecture. We see significant scaling in 3D rendering and ray tracing benchmarks, and although the Windows 11 Task Manager doesn’t distinguish between core types, it did show all 24 threads on the Core i9-12900K fully saturated during such tests.

Single-threaded performance also benefits tremendously, which means games will get a nice boost if you aren’t bottlenecked by your GPU. The Core i5-12600K strikes an interesting balance here – lots of cores, plus the architectural advantages that benefit lightly-threaded tasks. It’s expensive, by mid-range CPU standards, but could even be an upgrade over Core i7 and Core i9 models from the past few generations. This model is likely to be a hit with gamers.

One thing that does have to be noted is power consumption. Intel’s TDP rating system has changed to acknowledge that power draw is far higher than the rated level under stress, and now a CPU can run at turbo speed virtually unrestricted as long as your cooling solution is adequate. If you stress these CPUs for extended periods, you’ll be pulling a lot of power from your PSU (but also getting a lot done).

Automatic overclocking with the Asus TUF Gaming Z690-Plus Wifi D4 motherboard is as easy as selecting a few options in the BIOS and letting the system test its own limits. You could also use Intel’s Extreme Tuning Utility or Asus’ AI Suite 3 utilities through Windows. I was able to push the Core i9-12900K up to 5.3GHz on the P-cores and 4GHz on the E-cores in under a minute. The system ran perfectly stable and benchmarks ran fine, though the Strix cooler did run noticeably louder and ramp up to full speed much quicker.

After this minor overclock, CineBench R20’s single-core score rose from 760 to 791, and the multi-core score from 10,324 to 10,795. POVRay’s render time was cut from 29 seconds to 27 seconds, and the Corona rendering benchmark ran in 57 seconds, down from 1 minute, 18 seconds. An additional benchmark, NeroScore, which measures AI-powered photo tagging, produced a score of 2,584 before the overclock and 3,284 after. If you get into manual tweaking on a top-tier motherboard with DDR5 RAM, there’s sure to be more headroom to exploit.

There isn’t much to be said about Intel’s UHD 770 integrated GPU – performance gains over the previous generation are marginal. Even if you won’t get much use out of it, an integrated GPU is nice to have for troubleshooting and assembling. It could even be a lifesaver, considering the consumer-unfriendly GPU market we’re dealing with right now. For that reason, I’d always prefer a CPU with an iGPU over an -F variant – unless there’s a huge price difference.

![]()

The 12th Gen Core i9-12900K and Core i5-12600K excel when faced with a variety of workloads

Verdict

When the 11th Gen ‘Rocket Lake’ Core CPU family was launched in March this year, I called it a placeholder, since we already had a good idea of what Alder Lake was shaping up to be and when it would launch. Intel strongly refuted that characterisation, and the company’s logic was that those were the best CPUs for certain workloads available at the time – which, to be fair, was true. Ultimately, I advised people to hold off on a purchase if they could, since a lot was about to change.

If you have waited this long, you’ll be very glad. The 12th Gen is a considerable improvement in nearly all aspects of performance. This is the launch that will convince many people to upgrade from their current setups. It’s a roaring success for Intel after years of lacklustre updates, first because of a lack of competition and later because of its own internal problems. The advent of DDR5, PCIe 5.0, Windows 11, and heterogenous-core CPUs have injected new life into the PC market.

As far as content creation and multitasking go, you can’t go wrong with the new Alder Lake generation. The best news for buyers is that these unlocked 12th Gen Core CPUs aren’t priced out of reach – performance at mainstream prices in many cases exceeds that of the 18-core Core i9-10980XE, which was at one point considered a bargain at around Rs. 70,000, and that too was half the price of its predecessor. The Core i9-12900K puts Intel’s X-series out of commission, and it’s no surprise that a refresh hasn’t happened for the HEDT segment this year. If you want to do better, you’ll want to look at something like the Ryzen Threadripper series for massive brute-force all-core performance – but that’s a whole different market segment and pricing reflects that.

Intel hasn’t quite pulled off a decisive victory over AMD’s Ryzen 5000 series though – there are workloads that will still favour the Zen architecture with lots of cores, and we’ll have a new generation from the green team soon enough. Also keep in mind that you’ll need an expensive Z690 motherboard and DDR5 RAM to get the most out of the unlocked enthusiast SKUs released so far – when you add up all these prices, AMD could easily come out ahead for many people.

Intel Core i9-12900K

Price (approximate MOP): Rs. 60,000

Pros

- Excellent single- and multi-threaded performance

- DDR5, PCIe 5.0, fast platform-level IO

- Overclockable

Cons

- High platform cost

- Basic integrated graphics

- Power-hungry

- Potential compatibility issues

Ratings (out of 5)

- Performance: 4.5

- Value for Money: 4

- Overall: 4.5

Intel Core i5-12600K

Price (MOP): Rs. 31,500

Pros

- Excellent single- and multi-threaded performance

- DDR5, PCIe 5.0, fast platform-level IO

- Overclockable

Cons

- Expensive, high platform cost

- Basic integrated graphics

- Potential compatibility issues

Ratings (out of 5)

- Performance: 4

- Value for Money: 3.5

- Overall: 4

Asus TUF Gaming Z690-Plus Wifi D4

Price (MOP): Rs. 25,000

Pros

- Simple design, integrated IO shield, M.2 clamps

- Four M.2 slots, PCIe 5.0 x16 slot, USB 3.2×2 (20Gbps)

- Stable performance, easy auto overclocking

- Well-designed UEFI BIOS

Cons

- No BIOS failsafe or diagnostic display

Ratings (out of 5)

- Features: 4

- Performance: 4.5

- Value for Money: 4

- Overall: 4

[ad_2]

Source link